An LP’s perspective on benchmarking in venture capital

For many investors looking to invest in a venture capital fund, benchmarking is a key part of the due diligence process because it helps determine which managers have historically performed well against their peers. Typically, benchmarking is used when first deciding to make a new allocation to a fund. After an investment has been made, benchmarking may also be used to monitor a manager’s performance relative to other investment opportunities available to an investor.

Absolute versus relative benchmarking to help determine fund and asset allocation

When making a decision, we believe that many investors, including limited partners (LPs) such as Sapphire Ventures, think about both absolute and relative performance metrics. Many times, the absolute performance metric is important because investors, especially those investing in multiple asset classes, are making internal allocation decisions relative to the performance of other funds as well as other asset classes.

Therefore, if the venture capital performance of one fund is greater than any other venture capital fund but less than the performance of another asset class, perhaps the performance in general is less attractive for the investor to make the commitment to venture capital in her portfolio. Instead, we believe the investor may choose to invest in the relatively higher-performing asset class.

The decision making process for a follow-on investment in a fund may also depend on the relative performance of a fund compared to other funds already part of the same portfolio or new funds that could be added to the portfolio. For example, investors try to allocate to the top performers in the asset class and sometimes this means re-investing in existing managers already in the portfolio that have strong performance as well as investing in managers not yet in the portfolio that may have stronger results relative to the managers already in the portfolio. In effect, sometimes this decision on relative performance can lead to an investor replacing one manager with another.

Below are some of the metrics we use at Sapphire Ventures when performing our benchmarking analysis as well as some issues that make benchmarking a mixture of art and science.

Sapphire Ventures’ benchmarking metrics

Defined below, we believe that the most common four metrics used for venture capital investments are total value to paid in (TVPI), internal rate of return (IRR), distributed to paid in (DPI) and residual value to paid in (RVPI).

Total value to paid in (TVPI): the ratio of current value of remaining investments within a fund, plus the total value of all distributions to date, relative to the total amount of capital paid into the fund to date.

TVPI gives the investor a sense of what the cash-on-cash return is for a particular investment. That is, if $1 was invested, how much is the investor getting back from this investment net of fees and expenses. As mentioned earlier, a general rule of thumb is for each dollar committed (not only invested), the investor should get back $3.

Internal rate of return (IRR): the discount rate at which the net present value of the cash outflows (cost of the investments) and cash inflows (returns on the investment) equal zero.

IRR, which incorporates the time value of money, gives the average annual return earned during the life of the investment. In general, we believe investors should be rewarded with a premium that compensates for illiquidity and higher risk, and, in general, this return should be greater than 30 percent for a venture capital fund.

While many allocation decisions for investors are made based on both TVPI and IRR, we favor looking at TVPI because it should represent the multiple of money the investor is receiving back in her pocket at the end of the fund (an absolute number).

An IRR that is high for a fund early in its life cycle may be misleading, depending on the timing of the cash flow returns and NAVs, as we witnessed recently with Yale’s announcement on its venture capital performance. For a better understanding of how TVPI and IRR relate in practice, see Michael Roth’s Bison article IRR Can Be Useful — If You Know How To Use It.

Distributed to paid in (DPI): the ratio of money distributed to investors by the fund, relative to the total amount of capital paid into the fund to date.

We believe that DPI is important because it measures how much capital has been returned to investors to date. While TVPI represents the multiple of capital that could be realized, DPI actually states the capital realized and distributed by the fund.

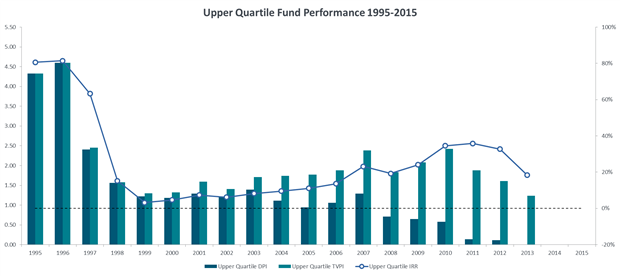

Below is a graph showing the upper quartile performance of the three metrics just discussed since 1995. As you can see, 1995 and 1996 were very attractive years for venture capital in terms of performance, while recent performance has been less attractive on an absolute basis. Note vintage years 2014 and 2015 are still too young for Cambridge to report meaningful performance benchmarks.

Source: Cambridge Associates

Residual value to paid in (RVPI): the ratio of the current value of all remaining investments within a fund, relative to the total amount of capital paid into the fund to date.

RVPI is one of the less often used metrics for benchmarking, though we believe that it should be assessed in terms of understanding the remaining upside within a portfolio. That is, if a fund has a relatively low RVPI with little remaining upside, an investor may use this information to determine whether they believe the fund will be a strong performer.

If the RVPI is low, but the manager of the fund is being conservative in how she values her position and the investor is fairly confident that there is future upside in the remaining positions in the portfolio, then the investor may be more likely to believe in the manager’s ability to find and invest in great companies despite a relatively low RVPI.

Having an expectation of what the RVPI of a portfolio can actually achieve in terms of performance over time is critically important. For example, amongst the various investments making up the value of the RVPI metric, understanding the concentration or dispersion of individual return drivers within the unrealized value portion of the portfolio is particularly useful.

For example, if all returns are being driven by just one company in a portfolio of 60 companies, then the investor may have difficulty believing the manager of the fund can consistently attract and invest in successful companies, even while understanding that venture capital portfolios are expected to have high loss ratios.

Limitations of benchmarking metrics

While the metrics introduced above are useful in gaining a sense of the performance of a manager, we believe that each metric has its limitations.

As mentioned earlier, TVPI does not take into account timing of cash flows. In short, not all 3x TVPI funds are created equal. We believe returning the same multiple faster is almost always preferred by the investor, while waiting 20 years to get 3x TVPI is less preferred. Because venture capital is a largely illiquid investment that requires a long lock-up period for the investor’s capital, looking at TVPI in relation to other metrics such as IRR and DPI can be useful for broadening an investor’s perspective on performance.

IRR takes into account the time value of money, but it can sometimes be misleading, especially if a company exits quickly in a portfolio. Because of how IRR is calculated, high IRRs do not always indicate great cash-on-cash performance, which is why looking at IRR vis-à-vis TVPI is helpful. As well, IRR is calculated using terminal values and terminal values are subjective metrics that can be imprecise.

DPI does not take into account the remaining value, or RVPI, of a portfolio. To determine the remaining upside potential in a portfolio, we think that it is important to look at this metric with respect to RVPI.

RVPI represents the unrealized value in a portfolio. At the end of a fund, an investor may not be able to actually get liquidity from a previously stated RVPI. That is, a high RVPI may be indicative of an inflated market versus an accurate representation of how much the portfolio can actually be sold for eventually. This issue of including unrealized values can also arise with other metrics.

Because TVPI, RVPI and IRR include unrealized performance, all of these metrics may be overstated in a bull market when company valuations are decoupled from reasonable comparables or precedent exit transactions. For example, recently many funds are showing great TVPI performance but much of the value remains unrealized, so the investor looking to invest in a venture capital fund with a high TVPI has to determine whether the metrics will hold over time based on rational expectations.

Also, the benchmarking metrics mentioned above, in particular TVPI and IRR, do not account for future contributions and distributions of a fund so the view of ultimate performance of a fund based on benchmarking analysis before the end of a fund is directional at best.

In addition, because standard definitions of the paid-in capital metrics are based on net values, residual values that do not account for carried interest or other additional expenses to be incurred by the fund in the future implies a discount is necessary to accurately assess the actual net performance of the fund.

Vintage benchmarking versus stage, geography and strategy

While most benchmarking for the metrics noted above are for vintage comparison, each fund that is being assessed may differ across a variety of characteristics. For example, we believe that a fund investing in seed-stage companies that raised in 2012 should not be compared to a fund that focuses on growth opportunities that also raised in 2012.

We think that this is also true for the stage of investments, geography and strategy of the fund. Each fund will have a different composition across initial stages of investments and overall exposure across various stages of investments. If this means that one fund has 75 percent exposure to Series B investments and another fund has only five percent exposure to Series B investments, these large differences may skew the comparison of the two funds based on just their respective vintages.

Ditto for geography and strategy. Typically an investor will go a step further after benchmarking based on vintage and compare the manager under scrutiny to a peer group of qualified managers that the investor considers a direct comparable set with respect to stage, geography and strategy.

Understanding the appropriate vintage benchmark

Within venture capital, a benchmark is typically created using a cohort of funds in a given vintage year. Some define vintage year as the legal inception year for the private investment fund, which is not always the year in which the first capital is invested. This means that some funds labeled as the same vintage may have very different investment schedules. For example, Fund A, a 2012 vintage fund, which started investing in January 2012, may have a very different investment timeline than Fund B, which closed in late 2012 but started investing in 2013.

In this example, the two funds would be compared apples-to-apples based on the same vintage, even though Fund A could have effectively another year of maturity in its underlying companies, which could affect its performance numbers relative to Fund B. We believe that one solution for this issue is comparing the fund in question to the benchmarking data from several vintages. That is, it may be useful to compare Fund A to benchmarks for 2011 and 2012 and Fund B to 2012 and 2013. Also, simply understanding the investment pacing of the funds in diligence and comparing them to an appropriate cohort of funds with similar deployment schedules may be informative.

Another issue that may be considered is the investment pacing of the manager. That is, Fund A may invest its full fund over two years while Fund B invests over five years. A direct comparison of the same vintage funds that employ different investment pacing can be misleading if the investor does not look into the actual timing of the outflows.

Relative benchmarking of venture capital using public market equivalent analysis

As mentioned earlier, many investors make relative decisions not only versus other funds within their venture capital portfolio, but among other asset classes as well. Public Market Equivalent (PME) analysis is one way to benchmark venture capital investments on a relative basis to public index investing. That is, investors ask whether it is better to invest in liquid public markets or commit capital to a blind pool that may remain liquid for more than 10 years.

Essentially PME analysis uses the cash flow data of a venture capital fund and compares the performance to public markets. For PME analyses, there are a number of methodologies, including Long Nickels, Kaplan Schoar and Direct Alpha (see Michael Roth’s blog on Making Sense of PMEs for more explanation), but all are effectively addressing whether contributions and distributions were part of an index fund (such as the Russell 2000) versus a venture capital investment. The Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation highlighted the importance of PME in the May 2012 report “We have met the enemy…and he is us”.

All in all, benchmarking is a very important piece of the due diligence process for investors. To stand out as a fund manager, we believe that performance must be strong across several metrics and be able to withstand the test of investors looking into the components of the performance. A manager that has created value and is well positioned to continue to create value is attractive to an investor on an absolute and relative basis, not only versus other managers, but also sometimes against other asset class investment options.